Examination of Cost Contribution Agreements (CCAs) in terms of transfer pricing

M. Akif Tunç

Zeynep Çelen

A CCA is a contractual arrangement among business enterprises to share the contributions and risks involved in the joint development, production or the obtaining of intangibles, tangible assets or services with the understanding that such intangibles, tangible assets or services are expected to create benefits for the individual businesses of each of the participants.

A CCA is a contractual arrangement rather than necessarily a distinct juridical entity or fixed place of business of all the participants. A CCA does not require the participants to combine their operations in order, for example, to exploit any resulting intangibles jointly or to share the revenues or profits. Rather, CCA participants may exploit their interest in the outcomes of a CCA through their individual businesses. The transfer pricing issues focus on the commercial or financial relations between the participants and the contributions made by the participants that create the opportunities to achieve those outcomes.

The contractual agreement provides the starting point for delineating the actual transaction. In this respect, no difference exists for a transfer pricing analysis between a CCA and any other kind of contractual arrangement where the division of responsibilities, risks, and anticipated outcomes as determined by the functional analysis of the transaction is the same.

A key feature of a CCA is the sharing of contributions. In accordance with the arm’s length principle, at the time of entering into a CCA, each participant’s proportionate share of the overall contributions to a CCA must be consistent with its proportionate share of the overall expected benefits to be received under the arrangement. Further, in the case of CCAs involving the development, production or obtaining of intangibles or tangible assets, an ownership interest in any intangibles or tangible assets resulting from the activity of the CCA, or rights to use or exploit those intangibles or tangible assets, is contractually provided for each participant. For CCAs for services, each participant is contractually entitled to receive services resulting from the activity of the CCA.

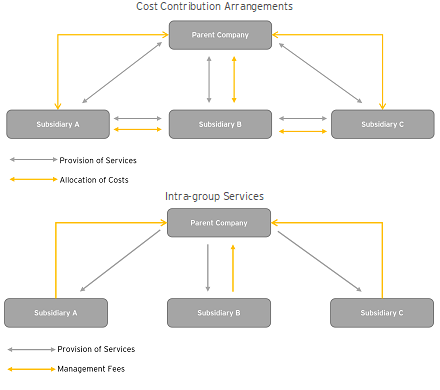

In practice it is sometimes difficult to differentiate between (shared) intra-group services - including cost pools - and CCAs on services not creating IP. The following figures is intended to help reviewers to differentiate between the two concepts1.

| CCAs on services not creating IP | Intra-group services |

| Agreement to share costs, risks and benefits where all participants contribute in cash or in kind. | Intra-group services are limited to the provision or acquisition of a service by members of the MNE Group. The risk of not successfully and efficiently providing the service is generally borne by the service provider. |

| If participants join or leave a CCA, shares should be adjusted/rebalanced in accordance with the ALP2. | Terminating or extending the service agreement to other participants has generally no implication on other service recipients. |

| Written agreements are highly recommended for reasons of having the CCA accepted or recognised by tax administrations. They are even compulsory in some MS. A written agreement and/or appropriate documentation is important for the reviewer when examining the implementation/performance of the CCA. | In practice, formal contracts are not always available. The agreement often is limited to the direct relationship between the provider and the recipient of the service. It should be feasible to demonstrate that from the perspective of the provider the service has been rendered and from the perspective of the recipient the service provides economic or commercial value to enhance his commercial position. |

| As all participants are contributing to a common activity and share costs and the contributions reflect the expected benefits, contributions are usually valued at costs. | The profit element charged by the provider of the service is usually a key element as the provider will not share profits with the recipients. |

| The allocation of the costs is based on the expected benefits for each participant from the CCA. | The allocation key is based on the extent each company has requested/received or is entitled to the service. |

Types of CCAs

Two types of CCAs are commonly encountered: those established for the joint development, production or the obtaining of intangibles or tangible assets (“development CCAs”); and those for obtaining services (“services CCAs”). Although each particular CCA should be considered on its own facts and circumstances, key differences between these two types of CCAs will generally be that development CCAs are expected to create ongoing, future benefits for participants, while services CCAs will create current benefits only.

Development CCAs, in particular with respect to intangibles, often involve significant risks associated with what may be uncertain and distant benefits, while services CCAs often offer more certain and less risky benefits. These distinctions are useful because the greater complexity of development CCAs may require more refined guidance, particularly on the valuation of contributions, than may be required for services CCAs, as discussed below. However, the analysis of a CCA should not be based on superficial distinctions: in some cases, a CCA for obtaining current services may also create or enhance an intangible which provides ongoing and uncertain benefits, and some intangibles developed under a CCA may provide short-term and relatively certain benefits.

Applying the arm’s length principle

For the conditions of a CCA to satisfy the arm’s length principle, the value of participants’ contributions must be consistent with what independent enterprises would have agreed to contribute under comparable circumstances given their proportionate share of the total anticipated benefits they reasonably expect to derive from the arrangement. What distinguishes contributions to a CCA from any other intra-group transfer of property or services is that part or all of the compensation intended by the participants is the expected mutual and proportionate benefit from the pooling of resources and skills.

In addition, particularly for development CCAs, the participants agree to share the upside and downside consequences of risks associated with achieving the anticipated CCA outcomes. As a result, there is a distinction between, say, the intra-group licensing of an intangible where the licensor has borne the development risk on its own and expects compensation through the licensing fees it will receive once the intangible has been fully developed, and a development CCA in which all parties make contributions and share in the consequences of risks materialising in relation to the development of the intangible and decide that each of them, through those contributions, acquires a right in the intangible.

The expectation of mutual and proportionate benefit is fundamental to the acceptance by independent enterprises of an arrangement for sharing the consequences of risks materialising and pooling resources and skills. Independent enterprises would require that the value of each participant’s proportionate share of the actual overall contributions to the arrangement is consistent with the participant’s proportionate share of the overall expected benefits to be received under the arrangement. To apply the arm’s length principle to a CCA, it is therefore a necessary precondition that all the parties to the arrangement have a reasonable expectation of benefit. The next step is to calculate the value of each participant’s contribution to the joint activity, and finally to determine whether the allocation of CCA contributions (as adjusted for any balancing payments made among participants) accords with their respective share of expected benefits. It should be recognised that these determinations are likely to bear a degree of uncertainty, particularly in relation to development CCAs. The potential exists for contributions to be allocated among CCA participants so as to result in an overstatement of taxable profits in some countries and the understatement of taxable profits in others, measured against the arm’s length principle. For that reason, taxpayers should be prepared to substantiate the basis of their claim with respect to the CCA.

Determining participants

Because the concept of mutual benefit is fundamental to a CCA, it follows that a party may not be considered a participant if the party does not have a reasonable expectation that it will benefit from the objectives of the CCA activity itself (and not just from performing part or all of the subject activity), for example, from exploiting its interest or rights in the intangibles or tangible assets, or from the use of the services produced through the CCA. A participant therefore must be assigned an interest or rights in the intangibles, tangible assets or services that are the subject of the CCA and have a reasonable expectation of being able to benefit from that interest or those rights. An enterprise that solely performs the subject activity, for example performing research functions, but does not receive an interest in the output of the CCA, would not be considered a participant in the CCA but rather a service provider to the CCA.

As such, it should be compensated for the services it provides on an arm’s length basis external to the CCA. Similarly, a party would not be a participant in a CCA if it is not capable of exploiting the output of the CCA in its own business in any manner.

A party would also not be a participant in a CCA if it does not exercise control over the specific risks it assumes under the CCA and does not have the financial capacity to assume these risks, as this party would not be entitled to a share in the output that is the objective of the CCA based on the functions it actually performs.

In particular, this implies that a CCA participant must have;

(i) the capability to make decisions to take on, lay off, or decline the risk-bearing opportunity presented by participating in the CCA, and must actually perform that decision-making function and

(ii) the the capability to make decisions on whether and how to respond to the risks associated with the opportunity and must actually perform that decision-making function.

It is not necessary for the CCA participants to perform all of the CCA activities through their own personnel. Such requirements include exercising control over the outsourced functions by at least one of the participants to the CCA. In cases where CCA activities are outsourced, an arm’s length charge would be appropriate to compensate the entity for services or other contributions being rendered to the CCA participants. Where the entity is an associated enterprise of one or more of the CCA participants, the arm’s length charge would be determined including inter alia consideration of functions performed, assets used, and risks assumed, as well as the special considerations affecting an arm’s length charge for services and/or in relation to any intangibles, (including the guidance on hard-to-value intangibles).

Expected benefits from the CCA

The relative shares of expected benefits might be estimated based on the anticipated additional income generated or costs saved, or other benefits received by each participant as a result of the arrangement. An approach that is frequently used in practice, most typically for services CCAs, would be to reflect the participants’ proportionate shares of expected benefits using a relevant allocation key. The possibilities for allocation keys include sales (turnover), profits, units used, produced, or sold; number of employees, and so forth.

To the extent that a material part or all of the benefits of a CCA activity are expected to be realised in the future and not solely in the year the costs are incurred, most typically for development CCAs, the allocation of contributions will take account of projections about the participants’ shares of those benefits. The use of projections may raise problems for tax administrations in verifying the assumptions based on which projections have been made and in dealing with cases where the projections vary markedly from the actual results. These problems may be exacerbated where the CCA activity ends several years before the expected benefits actually materialise. It may be appropriate, particularly where benefits are expected to be realised in the future, for a CCA to provide for possible adjustments of proportionate shares of contributions over the term of the CCA on a prospective basis to reflect changes in relevant circumstances resulting in changes in relative shares of benefits. In situations where the actual shares of benefits differ markedly from projections, tax administrations might be prompted to enquire whether the projections made would have been considered acceptable by independent enterprises in comparable circumstances, taking into account all the developments that were reasonably foreseeable by the participants, without using hindsight.

The value of each participant’s contribution and balancing payments

Under the arm’s length principle, the value of each participant’s contribution should be consistent with the value that independent enterprises in comparable circumstances would have assigned to that contribution. That is, contributions must generally be assessed based on their value at the time they are contributed, bearing in mind the mutual sharing of risks, as well as the nature and extent of the associated expected benefits to participants in the CCA, in order to be consistent with the arm’s length principle. Balancing payments may be made by participants to “top up” the value of the contributions when their proportionate contributions are lower than their proportionate expected benefits. Such adjustments may be anticipated by the participants upon entering into the CCA or may be the result of periodic re-evaluation of their share of the expected benefits and/or the value of their contributions.

For example;

Company A and Company B are members of an MNE3 group and decide to enter into a CCA. Company A performs Service 1 and Company B performs Service 2. Company A and Company B each “consume” both services (that is, Company A receives a benefit from Service 2 performed by Company B, and Company B receives a benefit from Service 1 performed by Company A).

Assume that the costs and value of the services are as follows:

| Costs of providing Service 1 (cost incurred by Company A) | 100 per unit |

| Value of Service 1 (i.e. the arm’s length price that Company A would charge Company B for the provision of Service 1) | 120 per unit |

| Costs of providing Service 2 (cost incurred by Company B) | 100 per unit |

| Value of Service 2 (i.e. the arm’s length price that Company B would charge Company A for the provision of Service 2) | 105 per unit |

In Year 1 and in subsequent years, Company A provides 30 units of Service 1 to the group and Company B provides 20 units of Service 2 to the group. Under the CCA, the calculation of costs and benefits are as follows:

| Cost to Company A of providing services (30 units * 100 per unit) | 3,000 (60% of total costs) |

| Cost to Company B of providing services (20 units * 100 per unit): | 2,000 (40% of total costs) |

| Total cost to group | 5,000 |

|

|

|

| Value of contribution made by Company A (30 units * 120 per unit): | 3,600 (63% of total contributions) |

| Value of contribution made by Company B (20 units * 105 per unit): | 2,100 (37% of total contributions) |

| Total value of contributions made under the CCA | 5,700 |

| Company A and Company B each consume 15 units of Service 1 and 10 units of Service 2: | |

| Benefit to Company A: | |

| Service 1: 15 units * 120 per unit | 1,800 |

| Service 2: 10 units * 105 per unit | 1,050 |

| Total | 2,850 (50% of total value of 5,700) |

|

| |

| Benefit to Company B: | |

| Service 1: 15 units * 120 per unit | 1,800 |

| Service 2: 10 units * 105 per unit | 1,050 |

| Total | 2,850 (50% of total value of 5,700) |

Under the CCA, the value of Company A and Company B’s contributions should each correspond to their respective proportionate shares of expected benefits, i.e., 50%. Since the total value of contributions under the CCA is 5,700, this means each party must contribute 2,850. The value of Company A’s in-kind contribution is 3,600 and the value of Company B’s in-kind contribution is 2,100. Accordingly, Company B should make a balancing payment to Company A of 750. This has the effect of “topping up” Company B’s contribution to 2,850; and offsets Company A’s contribution to the same amount.

If contributions were measured at cost instead of at value, since Companies A and B each receive 50% of the total benefits, they would have been required contribute 50% of the total costs, or 2 500 each, i.e., Company B would have been required to make a 500 (instead of 750) balancing payment to A.

In the absence of the CCA, Company A would purchase 10 units of Service 2 for the arm’s length price of 1,050 and Company B would purchase 15 units of Service 1 for the arm’s length price of 1,800. The net result would be a payment of 750 from Company B to Company A. As can be shown from the above, this arm’s length result is only achieved in respect of the CCA when contributions are measured at value4 .

[1] EU Joint Transfer Pricing Forum, Report on Cost Contribution Arrangements on Services not creating Intangible Property (IP) ,7 June 2012

[2] Arm’s Length Principle

[3] Multinational Enterprises

[4] OECD Transfer Pricing Guideline, 2022

Explanations in this article reflect the writer's personal view on the matter. EY and/or Kuzey YMM ve Bağımsız Denetim A.Ş. disclaim any responsibility in respect of the information and explanations in the article. Please be advised to first receive professional assistance from the related experts before initiating an application regarding a specific matter, since the legislation is changed frequently and is open to different interpretations.

Başa Dön

Başa Dön